COVID-19 in context: What can we learn from previous shocks to tertiary mobility?

I was delighted to participate in a webinar hosted by the Center for Studies in Higher Education at University of California, Berkeley on May 7, exploring the extent to which COVID-19 will shape international student mobility. The full seminar is available on YouTube, but I outline my thoughts on the ways in which the Asian financial crisis of 1997 might provide some insight into how sudden shocks can alter the trajectory of global student mobility below.

In 1665, the Bubonic Plague swept through—the first record of a pandemic disrupting higher education. Due to the pandemic, the University of Cambridge closed, and students went home to isolate. It was in this period that Sir Isaac Newton isolated at home, developed calculus and discovered the laws of gravity. I think it’s fair to say he was certainly much more productive than I have managed to be over my isolation period.

Previously, in the post-WWII era, there has been no analogue for COVID-19. The ways in which it has challenged higher education institutions, their educators, and their students are unprecedented. Since the 1970s, international student mobility at a global level has generally moved in a positive direction, accelerated by tailwinds like rising affluence around the globe, a lack of local capacity, and the advent of mass air-travel.

Global student mobility has also been on the receiving end of severe shocks—not the least of which was 9/11, which depressed the numbers of foreign students studying in the United States for three years. However, China also joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, accelerating massive growth in the numbers of Chinese students going abroad for their education—a phenomenon which persists to this day, although the growth is no longer on the same scale as in earlier years.

Ironically, the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 led to an acceleration in mobility—particularly to the U.S. Why did it accelerate growth? Partially, because public universities in the U.S. experienced major cuts in state government support, which has endured for a decade. As well as increasing tuition, many universities turned to out-of-state and international students to help compensate for the decline in public funds. This, in turn, led to a much more active, intentional approach to international student recruitment as well as the creation of dedicated programming to support student success.

Asian Currency Crisis: Adjusting the trajectory of student mobility

There is, however, one event which may offer insight into how sudden, global shocks can adjust the trajectory of mobility. In the mid-1990s, I worked in the international office of Liverpool John Moores University in the United Kingdom. It was a time before China had emerged as a dominant sending country for the U.K., and when the numbers of Indian students had yet to make a meaningful impact on international student statistics. Instead, most active international recruitment focused on the Arab Gulf countries and southeast Asia—Hong Kong, Singapore, Brunei and, most importantly, Malaysia.

As a ‘post-1992’ university, created from Liverpool Polytechnic, growing international enrollments was both a revenue driver and a mark of our newly acquired status as a university. As a challenger brand, it led to much innovation, including 18-month degree programs designed for transfer students with credit from private Malaysian institutions and January starts for degrees, better aligning the proposition with their local academic calendar.

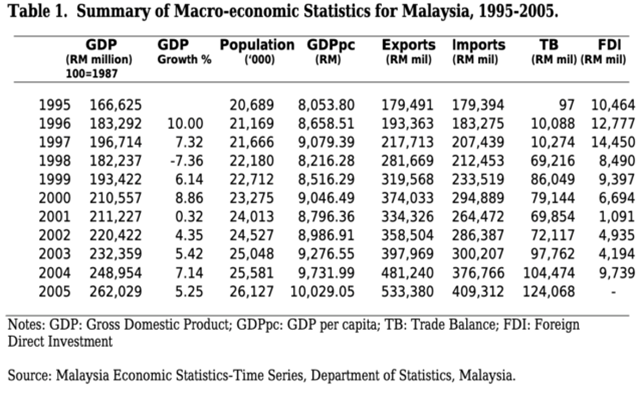

At the time, Malaysia was the most important source country for both Australian and British universities. There were almost nine times more Malaysians (18,000) studying in the U.K. than there were Chinese students (2,600). In fact, there were almost three times more students from Singapore in the U.K and Australia than from India. Then, in 1997, the Asian Currency Crisis hit, leading to a recession in Thailand, Malaysia, and across South East Asia, the so-called Asian Tiger economies. In Malaysia, gross domestic product (GDP) declined by 7.4% in 1998. The value of Malaysian currency against the U.S. dollar almost halved, with GDP per capita not fully recovering for five to six years.

The number of Malaysian students traveling to the UK decreased by almost half between 1997 and 2002, and it was five years before Chinese student enrolments matched the 1997 numbers from Malaysia.

Between 1998 and 2005, the number of Malaysian students studying in the U.S. also fell by 50%. Thai student enrollments fell by 43% over the same period, and they continued to do so for a decade. But it was the contraction few noticed in the U.S. because it coincided with the rise of China and, to a lesser extent, India as international student sources, which more than compensated for the decline in Malaysian and Thai student enrolments.

In the region, as outbound mobility decreased, gross enrolment ratios—participation in locally delivered HE provision—increased. The education economist and researcher Janet Ilieva tracked the inverse relationships between mobility and Gross Enrollment in a report released at the Australia International Education Conference in 2017.

It is no accident that Monash University opened its first overseas campus in Malaysia in 1998, or that the University of Nottingham chose Malaysia to become the U.K.’s first overseas campus in 2000.

Twenty years on from the Asian financial crisis, southeast Asia is now a destination hub in its own right—Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand each offer an ecosystem of world class universities, a vibrant private sector which in turn supports the presence of large public universities from other parts of the world, and a variety of offshore campuses from Western countries. This is as evident in K-12 as it is in tertiary education. Thailand in particular is home to a large contingent of international private schools attracting students from throughout the wider region. And, even with this level and diversity of local provision, there are still very many students who choose to go overseas for their secondary and tertiary education.

This economic crisis did not change the course of mobility, but it accelerated change already in place, precipitated by sudden change in economic fortunes in the region and a recognition, I would argue, that the universities now dependent on the revenue from this region needed to innovate to remain accessible to the region.

During the Asian Currency Crisis, there were approximately 1.8 million globally mobile students. More than 20 years later that number has tripled to 5.3 million. So, one has to wonder how the shape of mobility will change as a consequence of COVID-19.

There will certainly be change given the sheer scale of demand for high quality, life-changing education. But it may not be a black swan moment for online education. Online instruction and/or degrees are a bridge to the future, but they won’t deliver a total replacement for the traditional campus—especially for international students seeking an immersive social and cultural experience, and the opportunity to rapidly enhance language skills. Likewise, lowering entrance requirements to compete for students in a cutthroat market is not a strategy for excellence, especially given increased complexity of supporting students remotely. COVID-19 may act as a direct barrier to mobility over the short term, but over the longer term, it is likely to have a more enduring economic legacy, which may be felt in deeper and more disruptive ways across different parts of the world.

This could be an opportunity for a serious recalibration and redesign of Higher Education for a Global Age, with further, regionally-targeted innovation enhancing options for students seeking access to higher education outside their home nation. COVID-19 will be a catalyst for the continued evolution of a global higher education system where world class universities compete for and serve a global student population. Anyone who is longing for a return to normal is likely to be disappointed and ill-prepared for what lies ahead. But given the changes that have occurred already over the last two decades, what is, or was normal? As they say, we should never let a good crisis go to waste!